The Curious Case of Patent Balance Sheet Invisibility

IPO’s and M&A are back on Wall Street, and a slew of tech IPO’s at that. And while companies polish their balance sheets in hopes of capital markets success, try as you might a company’s patents are virtually invisible on corporate books. Despite this, patents have been identified as potentially playing a key role in invariably promoting or retarding deals subject to regulatory review in cases of technologies critical to national security or in response to public health crises such as by pooling. In the age of transparency, wouldn’t it be important to know the economic value of what is at stake? Economically speaking as to patents, if you can’t measure it, you can’t control it. That is a sad statement to make as to an entire class of modern society’s most valuable assets.

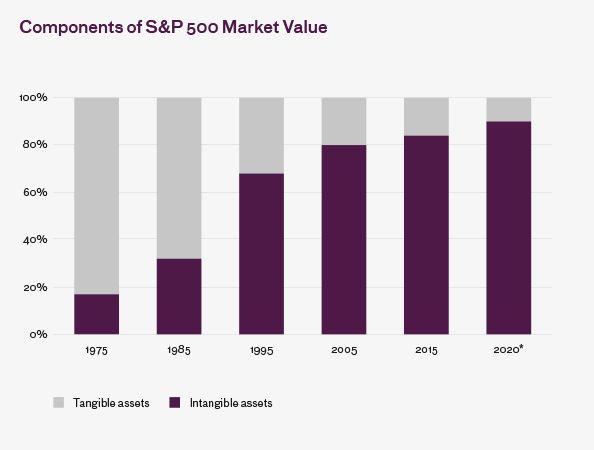

Indeed, patent invisibility is all the more puzzling when you consider that, since 1995, the predominant component of market capitalization of companies comprising the S&P 500 is not the green-shade favorite of plant, equipment and tangible assets, but rather intangible assets – generally, intellectual property protectable as copyrights, trademarks – and, yes, patents1. Trade secret protection for companies remains a viable option – such as the formula for Coca-Cola – yet as between patents and trade secrets, government patent programs incentivize patent protection, and the markets prefer it. Patents in-and-of-themselves may have value for licensing, yet they are at their most valuable when they cover a real economy good or service produced under it, allowing for government sanctioned monopoly profits. Yet, look at any balance sheet of any technology company lining up to go public or even those that have been long public and, with few exceptions, you’ll see nary a patent, let alone any disciplined accounting treatment of it.

And while companies polish their balance sheets in hopes of capital markets success, try as you might a company’s patents are virtually invisible on corporate books

In the M&A context, particularly when it comes to international investment in U.S. companies that requires approval by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S. (known as “CFIUS”), lack of accounting treatment for patents makes the evaluation of so-called ‘critical technologies’ raising national security issues all the more difficult because it’s unclear how a company values its intellectual property covering those technologies.

Commercially, without transparency as to a company’s marked-to-market reports of what its patents are worth makes concerted collective action – such as standard setting and patent pooling – all the more difficult. Indeed, as Nobel Laurate Joseph Stiglitz suggests on these companion pages, if patent pooling and ready rights access can hasten technologies to the public in response to public health crises, such as the current COVID-19 global pandemic, then transparency as the value of rights contributed to the pool, can promote deal making. In this way, sunshine can be both the best disinfectant and deal-accelerant.

Accountants would tell you that lack of GAAP2 standards is the culprit conveniently enough, but to a large extent that merely begs the question. While Wall Street can wax eloquent about strange beasts called non-priced alternative investments, when it comes to patents, accountants and bankers alike are tongue-tied. It is time for that to change.

Source: Ocean Tomo, LLC Intangible

Asset Market Value Study, 2020

*Interim study update as of 7/1/2020

The Patent-curious Case for Treatment Alternative Investments

Ocean Tomo, an intellectual property merchant bank, has tracked the relative percentage of value of tangible assets (land, plant, and equipment) to intangible assets (copyrights, trademarks, and patents) over the last four decades. The results are remarkable; the inversion of intangible assets overtaking tangible as a matter of corporate value occurred between 1985 and 2000.

Indeed, Ocean Tomo updated its study to account for the measurable economic impact of COVID-19 and found that the pandemic in fact accelerated the trend toward intangible assets, with intangible assets now presenting over 90% of the S&P500 market value.

In Asian markets, however, including in China, Japan, and South Korea, their observation has been a decline as evidenced by the Shanghai Shenzen CSI 300, the Nikkei 225, and KOSDAQ Composite Index, respectively. As to the decline, reporting differences as to COVID-19 cases stemming from various countries and difficulties in economic correlation were noted.

Might such analysis – and even positive collective action, such as pooling, fueled by measurable metrics such as the effect of the global pandemic on intangible assets – be aided by consistent accounting treatment and balance-sheet transparency?

Patents Un-Siloed:

As to patents, some companies, notably IBM, consistently drop billions of dollars in revenue to the bottom line from its global licensing program. As to licensing, legendary IBM, then Microsoft’s IP lawyer Marshall Phelps has famously recounted the story of open innovation and licensing at IBM, whereby he informed his new CEO – Lou Gerstner – that he planned to license IBM’s massive patent portfolio to the marketplace. Mr. Phelps’s team then exposed an IBM laptop circuit board and inserted a flag into every component representing someone else’s patent. Mr. Phelps’s story vividly illustrates the interdependence and interoperability of patents and products they cover in complex value chains. Mr. Phelps ran out of flags – and room to insert them – at 100.

While patent licensing is revenue derived from a company’s completely legal means of ordering the market, it doesn’t tell us the ‘price’ or the value of a patent as an asset per se. As a result, licensing revenues do not fully inform or provide a price discovery mechanism (for example, what if the patents are not licensed?) as to the intrinsic value of the patent – as an asset per se.

In the financial world, ‘price discovery’ is normally difficult for alternative assets. For patents, it has been virtually non-existent and that has led to a speculation-laden arbitrage swamp, which in turn has led to the vilification of entities that do not produce products or services under their own patents as ‘trolls’. This is a result where patent holders provide no direct economic contribution at all – where there are no operations directed to real economy goods and services. The U.S. Supreme Court noted this valuation conundrum well over a decade ago in the U.S. when evaluating the so-called ‘automatic injunction’ rule believed to be the inexorable result of a court finding of infringement. Justice Kennedy noted valuation difficulties in a famous concurrence in the eBay v. MercExchange case that:

[i]n many cases now arising…the nature of the patent being enforced and the economic function of the patent holder present considerations quite unlike earlier cases. And industry has developed in which firms use the patents not as a basis for producing and selling goods, but, instead, primarily for obtaining licensing fees.

In more mature and research development intensive industries – such as manufacturing or pharmaceuticals – patent valuation tends to bear a tighter correlation to economic value. But in less mature and especially more ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ technology-intensive industries, the economic equation – even if there is one – falters and remains virtually balance-sheet invisible as a corporate intangible asset.

If patents are to be considered an asset, then they are an asset that is off-balance sheet and, non-priced, as an “Alternative Asset,” one that does not conform to traditional asset class notions like stocks and bonds. Because alternative assets are not very liquid, valuation can be difficult.

An Investment Lens For Patent Transparency

What makes patents ‘alternative’ in the realm of financing is their nature as a legal property right of sorts. To enforce a patent is to incur steep litigation costs to try your action in court and hope for a favorable but post-facto infringement determination by a deciding court.

If a patent holder successfully enforces its patent, notably the legal ‘valuation’ occurs AFTER – sometimes years – a trial on the merits.

As a result, early notions of this time-warped ‘patent market’ looked and felt like an enormous arbitrage play. That is, with the sticker-shock-high cost of patent litigation and the inherent post-facto timing of a court outcome, patent market ‘forces’ remain untethered to any real economy underpinnings.

Currently, however, banks, private equity players and hedge funds have started to provide financing strategies which move beyond royalty securitizations and treat, deploy, and realize sustainable returns on patents as assets-per se. For example, patent-backed loans can be structured due to a better, up-front and more ‘market friendly’ valuation mechanism – based upon credit-return models – to become effectively more ‘liquid.’

Models are being developed that analogize patent rights asset as a quasi-financial instrument in and of itself. The instrument? Well, derivatives, of course (this is Wall Street, after all) since the very essence of patent is that it derives its value from its enforceability against real-economy produced goods and services.

Such market-friendlier monetization alternatives have become available because patent-as-derivatives can be valued in absentia of a transaction. This approach relies on market forces and calculating compensation to the patent owner. The patent maps (recall Mr. Phelps’ flags) that need to be created for patent valuation can and should highlight the correlation between the ‘patent rights world’ and the ‘real-economy’ goods and services world that patent claims cover. If this is done right, then better patent ‘price discovery’ and market efficiencies will result since such a mapping process ‘prices’ patents granularly relating to specific claim sets’ derivative-based fundamentals (that is, the real-economy value driver).

This in turn would beget more consistent accounting treatment and allow for more balance-sheet transparency of intangible assets. And this would benefit investors not only in U.S. public companies but also corporate deals on the international front.

Particularly with the U.S. and China international agreements as to intellectual property, patent balance-sheet transparency could aid in U.S. CFIUS review of international mergers, acquisitions or takeovers by enabling better determinations of the drivers of the deal rationale. With such transparency, valuation could become more standardized as to the illusive intangible assets that patents represent. This, in turn, could aid in determining more precisely national security risks as presented by investment and exactly which intangible assets are valuable and to what extent by the putative international investor.

As to promoting desirable collective behavior, such as cross-licensing or patent pooling, a GAAP-like, consistent accounting treatment would provide a market-based view and valuation of the patent rights

being contributed

Finally, as to promoting desirable collective behavior, such as cross-licensing or patent pooling, a GAAP-like, consistent accounting treatment would provide a market-based view and valuation of the patent rights being contributed. The market confidence that would arise from such valuations would reduce deal friction by promoting transparency and tighter correlation as to both rights and hard technologies pooled.

Consistent balance-sheet accounting treatment of patents as corporate assets would increase comfort and confidence across the board, be it in a CFIUS review or a pooling negotiation. It would provide current, market-based information that has heretofore been largely guesswork.

References

- Ocean Tomo report: http://www.oceantomo.com/intangible-asset-market-value-study/

- Generally Accepted Accounting Principles: http://www.investopedia.com/terms/g/gaap.asp